Euler's three-body problem

In physics and astronomy, Euler's three-body problem is to solve for the motion of a particle that is acted upon by the gravitational field of two other point masses that are either fixed in space or move in circular coplanar orbits about their center of mass. This problem is significant as an exactly soluble special case of the three-body problem, and an approximate solution for particles moving in the gravitational fields of prolate and oblate spheroids. This problem is named after Leonhard Euler, who discussed it in memoirs published in 1760. Important extensions and analyses were contributed subsequently by Lagrange, Liouville, Laplace, Jacobi, Darboux, Le Verrier, Velde, Hamilton, Poincaré, Birkhoff and E. T. Whittaker, among others.[1]

Euler's problem also covers the case when the particle is acted upon by other inverse-square central forces, such as the electrostatic interaction described by Coulomb's law. The classical solutions of the Euler problem have been used to study chemical bonding, using a semiclassical approximation of the energy levels of a single electron moving in the field of two atomic nuclei, such as the diatomic ion HeH2+. This was first done by Wolfgang Pauli in his doctoral dissertation under Arnold Sommerfeld, a study of the first ion of molecular hydrogen, namely the Hydrogen molecule-ion H2+.[2] These energy levels can be calculated with reasonable accuracy using the Einstein-Brillouin-Keller method, which is also the basis of the Bohr model of atomic hydrogen.[3][4] More recently, as explained further in the quantum-mechanical version, analytical solutions to the eigenenergies have been obtained: these are a generalization of the Lambert W function.

By treating Euler's problem as a Liouville dynamical system, the exact solution can be expressed in terms of elliptic integrals.[5][6] For convenience, the problem may also be solved by numerical methods, such as Runge–Kutta integration of the equations of motion. The total energy of the moving particle is conserved, but its linear and angular momentum are not, since the two fixed centers can apply a net force and torque. Nevertheless, the particle has a second conserved quantity that corresponds to the angular momentum or to the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector as limiting cases.

The Euler three-body problem is known by a variety of names, such as the problem of two fixed centers, the Euler-Jacobi problem, and the two-center Kepler problem. It is also called the circular restricted three-body problem, as it is a special case of the general three-body problem in which the two massive particles have zero orbital eccentricity and the third particle is "restricted" to have negligible mass. Special cases of this problem include the Copenhagen problem (where the two large masses are equal) and the Pythagorean problem (where the three bodies have initial masses in the ratio 3:4:5 and prescribed initial positions). Various generalizations of Euler's problem are known; these generalizations add linear and inverse cubic forces and up to five centers of force. Special cases of these generalized problems include Darboux's problem[7] and Velde's problem.[8]

Contents |

Overview and history

Euler's three-body problem is to describe the motion of a particle under the influence of two centers that attract the particle with central forces that decrease with distance as an inverse-square law, such as Newtonian gravity or Coulomb's law. Examples of Euler's problem include a planet moving in the gravitational field of two stars, or an electron moving in the electric field of two nuclei, such as the first ion of the hydrogen molecule, namely the hydrogen molecule-ion H2+. The strength of the two inverse-square forces need not be equal; for illustration, the two attracting stars may have different masses, and the two nuclei may have different charges, as in the molecular ion HeH2+.

This problem was first considered by Leonhard Euler, who showed that it had an exact solution in 1760.[9] Joseph Louis Lagrange solved a generalized problem in which the centers exert both linear and inverse-square forces.[10] Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi showed that the rotation of the particle about the axis of the two fixed centers could be separated out, reducing the general three-dimensional problem to the planar problem.[11]

Constants of motion

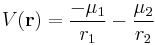

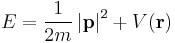

The problem of two fixed centers conserves energy; in other words, the total energy E is a constant of motion. The potential energy is given by

where r represents the particle's position, and r1 and r2 are the distances between the particle and the centers of force; μ1 and μ2 are constants that measure the strength of the first and second forces, respectively. The total energy equals sum of this potential energy with the particle's kinetic energy

where m and p are the particle's mass and linear momentum, respectively.

The particle's linear and angular momentum are not conserved in Euler's problem, since the two centers of force act like external forces upon the particle, which may yield a net force and torque on the particle. Nevertheless, Euler's problem has a second constant of motion

where 2a is the separation of the two centers of force, θ1 and θ2 are the angles of the lines connecting the particle to the centers of force, with respect to the line connecting the centers. This second constant of motion was identified by E. T. Whittaker in his work on analytical mechanics,[12] and generalized to n dimensions by Coulson and Joseph in 1967.[13] In the Coulson-Joseph form, the constant of motion is written

This constant of motion corresponds to the total angular momentum |L|2 in the limit when the two centers of force converge to a single point (a → 0), and proportional to the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector A in the limit when one of the centers goes to infinity (a→∞ while x-a remains finite).

Quantum mechanical version

A special case of the quantum mechanical three-body problem is the Hydrogen molecule-ion  . Two of the three bodies are nuclei and the third is a fast moving electron. The two nuclei are 1800 times heavier than the electron and thus modeled as fixed centers. It is well known that the Schrödinger wave equation is separable in Prolate spheroidal coordinates and can be decoupled into two ordinary differential equations coupled by the energy eigenvalue and a separation constant. [14] However, solutions required series expansions from basis sets. Nonetheless, through experimental mathematics, it was found that the energy eigenvalue was mathematically a generalization of the Lambert W function [15] (see Lambert W function and references therein for more details). The hydrogen molecular ion in the case of clamped nuclei can be completely worked out within a Computer algebra system. The fact that its solution is an implicit function is revealing in itself. One of the successes of theoretical physics is not simply a matter that it is amenable to a mathematical treatment but that the algebraic equations involved can be symbolically manipulated until an analytical solution, preferably a closed form solution, is isolated. This type of solution for a special case of the three-body problem shows us the possibilities of what is possible as an anaytical solution for the quantum three-body and many-body problem.

. Two of the three bodies are nuclei and the third is a fast moving electron. The two nuclei are 1800 times heavier than the electron and thus modeled as fixed centers. It is well known that the Schrödinger wave equation is separable in Prolate spheroidal coordinates and can be decoupled into two ordinary differential equations coupled by the energy eigenvalue and a separation constant. [14] However, solutions required series expansions from basis sets. Nonetheless, through experimental mathematics, it was found that the energy eigenvalue was mathematically a generalization of the Lambert W function [15] (see Lambert W function and references therein for more details). The hydrogen molecular ion in the case of clamped nuclei can be completely worked out within a Computer algebra system. The fact that its solution is an implicit function is revealing in itself. One of the successes of theoretical physics is not simply a matter that it is amenable to a mathematical treatment but that the algebraic equations involved can be symbolically manipulated until an analytical solution, preferably a closed form solution, is isolated. This type of solution for a special case of the three-body problem shows us the possibilities of what is possible as an anaytical solution for the quantum three-body and many-body problem.

Generalizations

An exhaustive analysis of the soluble generalizations of Euler's three-body problem was carried out by Adam Hiltebeitel in 1911. The simplest generalization of Euler's three-body problem is to augment the inverse-square force laws with a force that increases linearly with distance. The next generalization is to add a third center of force midway between the original two centers, that exerts only a linear force. The final set of generalizations is to add two fixed centers of force at positions that are imaginary numbers, with forces that are both linear and inverse-square laws, together with a force parallel to the axis of imaginary centers and varying as the inverse cube of the distance to that axis.

The solution to the original Euler problem is an approximate solution for the motion of a particle in the gravitational field of a prolate body, i.e., a sphere that has been elongated in one direction, such as a cigar shape. The corresponding approximate solution for a particle moving in the field of an oblate spheroid (a sphere squashed in one direction) is obtained by making the positions of the two centers of force into imaginary numbers. The oblate spheroid solution is astronomically more important, since most planets, stars and galaxies are approximately oblate spheroids; prolate spheroids are very rare.

Mathematical solutions

Original Euler problem

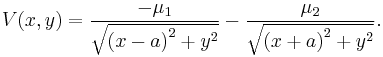

In the original Euler problem, the two centers of force acting on the particle are assumed to be fixed in space; let these centers be located along the x-axis at ±a. The particle is likewise assumed to be confined to a fixed plane containing the two centers of force. The potential energy of the particle in the field of these centers is given by

where the proportionality constants μ1 and μ2 may be positive or negative. The two centers of attraction can be considered as the foci of a set of ellipses. If either center were absent, the particle would move on one of these ellipses, as a solution of the Kepler problem. Therefore, according to Bonnet's theorem, the same ellipses are the solutions for the Euler problem.

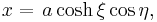

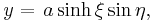

Introducing elliptic coordinates,

the potential energy can be written as

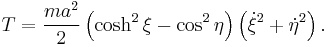

and the kinetic energy as

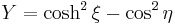

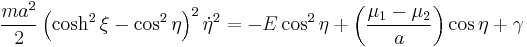

This is a Liouville dynamical system if ξ and η are taken as φ1 and φ2, respectively; thus, the function Y equals

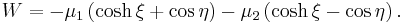

and the function W equals

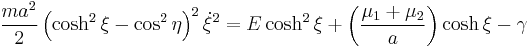

Using the general solution for a Liouville dynamical system,[16] one obtains

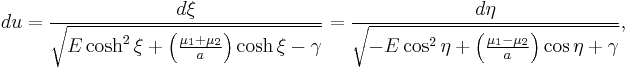

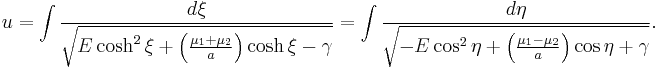

Introducing a parameter u by the formula

gives the parametric solution

Since these are elliptic integrals, the coordinates ξ and η can be expressed as elliptic functions of u.

See also

- Jacobi integral

- Lagrangian point

- Three-body problem

- Liouville dynamical system

- Hydrogen molecular ion

References

- ^ Carl D. Murray & Stanley F. Dermott (2000). Solar System Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. Chapter 3. ISBN 0521575974. http://books.google.com/?id=aU6vcy5L8GAC&pg=PA63&dq=%22restricted+three-body+problem%22.

- ^ Pauli W (1922). "Über das Modell des Wasserstoffmolekülions". Annalen der Physik 68: 177–240.

- ^ Knudson SK (2006). "The Old Quantum Theory for H2+: Some Chemical Implications". Journal of Chemical Education 83 (3): 464–472. Bibcode 2006JChEd..83..464K. doi:10.1021/ed083p464.

- ^ Strand MP, Reinhardt WP (1979). "Semiclassical quantization of the low lying electronic states of H2+". Journal of Chemical Physics 70 (8): 3812–3827. Bibcode 1979JChPh..70.3812S. doi:10.1063/1.437932.

- ^ Whittaker ET (1937). A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, with an Introduction to the Problem of Three Bodies (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 97–99. ISBN 0521358833. ASIN B0006AQI82. http://books.google.com/?id=OSckAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22A+Treatise+on+the+Analytical+Dynamics+of+Particles+and+Rigid+Bodies%22.

- ^ Alessandra Celletti & Luigi Chierchia (2007). Kam Stability and Celestial Mechanics. American Mathematical Society Bookstore. Chapter 3. ISBN 0821841696. http://books.google.com/?id=hiuyvc-XoOwC&pg=PA75&dq=%22restricted+three-body+problem%22.

- ^ Darboux JG, Archives Néerlandaises des Sciences (ser. 2), 6, 371–376

- ^ Velde (1889) Programm der ersten Höheren Bürgerschule zu Berlin

- ^ Euler L, Nov. Comm. Acad. Imp. Petropolitanae, 10, pp. 207–242, 11, pp. 152–184; Mémoires de l'Acad. de Berlin, 11, 228–249.

- ^ Lagrange JL, Miscellanea Taurinensia, 4, 118–243; Oeuvres, 2, pp. 67–121; Mécanique Analytique, 1st edition, pp. 262–286; 2nd edition, 2, pp. 108–121; Oeuvres, 12, pp. 101–114.

- ^ Jacobi CGJ, Vorlesungen ueber Dynamik, no. 29. Werke, Supplement, pp. 221–231

- ^ Whittaker, p. 283.

- ^ Coulson CA, Joseph A (1967). "A Constant of Motion for the Two-Centre Kepler Problem". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 1 (4): 337–447. Bibcode 1967IJQC....1..337C. doi:10.1002/qua.560010405.

- ^ G.B. Arfken, Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 2nd ed., Academic Press, New York (1970).

- ^ T.C. Scott, M. Aubert-Frécon and J. Grotendorst (2006). "New Approach for the Electronic Energies of the Hydrogen Molecular Ion", Chem. Phys. 324: 323-338, [1]; Arxiv article [2]

- ^ Liouville J (1849). "Mémoire sur l'intégration des équations différentielles du mouvement d'un nombre quelconque de points matériels". Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées 14: 257–299. http://visualiseur.bnf.fr/ConsulterElementNum?O=NUMM-16393&Deb=263&Fin=305&E=PDF.

Further reading

- Hiltebeitel AM (1911). "On the Problem of Two Fixed Centres and Certain of its Generalizations". American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 33 (1/4): 337–362. doi:10.2307/2369997. JSTOR 2369997.

- Erikson HA, Hill EL (1949). "A Note on the One-Electron States of Diatomic Molecules". Physical Review 75: 29–31. Bibcode 1949PhRv...75...29E. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.75.29.

- Corben HC, Stehle P (1960). Classical mechanics. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 206–213. ISBN 0-88275-162-X.

- Howard JE, Wilkerson TD (1995). "Problem of two fixed centers and a finite dipole: A unified treatment". Physical Review A 52 (6): 4471–4492. Bibcode 1995PhRvA..52.4471H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.4471. PMID 9912786.

- Knudson SK, Palmer IC (1997). "Semiclassical electronic eigenvalues for charge asymmetric one-electron diatomic molecules: general method and sigma states". Chemical Physics 224: 1–18. Bibcode 1997CP....224....1K. doi:10.1016/S0301-0104(97)00226-7.

- José JV, Saletan EJ (1998). Classical dynamics: a contemporary approach. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 298–300, 378–379. ISBN 0-521-63176-9.

- Nash PL, Lopez-Mobilia R (1999). "Quasielliptical motion of an electron in an electric dipole field". Physical review E 59 (4): 4614–4617. Bibcode 1999PhRvE..59.4614N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.59.4614.

- Waalkens H, Dullin HR, Richter PH (2004). "The problem of two fixed centers: bifurcations, actions, monodromy". Physica D 196 (3-4): 265–310. Bibcode 2004PhyD..196..265W. doi:10.1016/j.physd.2004.05.006.

![r_{1}^{2} r_{2}^{2} \left( \frac{d\theta_{1}}{dt} \right) \left( \frac{d\theta_{2}}{dt} \right) -

2a \left[ \mu_{1} \cos \theta_{1} %2B \mu_{2} \cos \theta_{2} \right],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5c3f77538466f72928f6b72145db6ac4.png)

![B = \left| \mathbf{L} \right|^{2} %2B a^{2} \left| \mathbf{p} \right|^{2}

-2a \left[\mu_{1} \cos \theta_{1} %2B \mu_{2} \cos \theta_{2} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3920acfe1d47a4940610f70336dfe380.png)

![\begin{align}

V(\xi, \eta) & = \frac{-\mu_{1}}{a\left( \cosh \xi - \cos \eta \right)} - \frac{\mu_{2}}{a\left( \cosh \xi %2B \cos \eta \right)} \\[8pt]

& = \frac{-\mu_{1} \left( \cosh \xi %2B \cos \eta \right) - \mu_{2} \left( \cosh \xi - \cos \eta \right)}{a\left( \cosh^{2} \xi - \cos^{2} \eta \right)},

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/14eb78c026b997d748837b3117e1379f.png)